Verdad Magazine Volume 18

Spring 2015, Volume 18

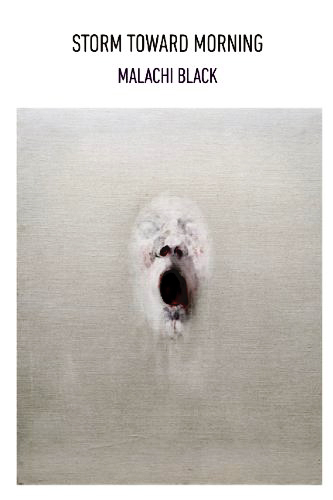

Storm Toward Morning by Malachi Black

Review by Bill Neumire

In the middle ring of the 7th circle of Dante’s vision of Hell, harpies in the wood of suicides eternally feed from the leaves of oak trees which entomb “self-murderers.” Cut to Malachi Black’s debut, Storm Toward Morning, which opens with Cardinal Wosley’s ominous lines, “I shall fall / like a bright exhalation in the evening, / And no man see me more” from Shakespeare’s Henry VIII. Black’s collection is a modern Inferno chapter with a speaker caught in a test of faith—at turns convinced he sees God “in the wind” and then a moment later convinced it’s just the wind, and then again sure the wind has “intention.” Taking pills and vodka, the forlorn, existentially-troubled speaker of these metrically-driven poems is so caught in this argument with himself, so desperate to prove there’s a god, that he “cuts himself into a cave” for the Lord. The speaker writes:

you are the tongueI plunge into this begging

razorblade so brightened

by my spiderweb of blood,

you are the one: you are

the venom in the serpent

I have tried not to become,

my Lord. You are the one (35).

Frustrated, angry, determined to penetrate God’s silence, it’s a speaker who, like all great believers, suffers from periodic doubt, who questions god. It’s a journey from life to suicide to afterlife, the epic hero’s (or anti-hero’s) journey through the underworld to gain critical perspective. And though the speaker is suicidal, it is not self-pitying so much as seeking an affirmation, a connection to god and the eternal, for an answer to what happens after death:

Now there is nothing I can touch(…)

I’ll clutch

whatever I remember

of the seasons I let skip

across the playground of my blood

and then let go: this is the fall,

and something falling’s all I know—

my own old footprints filling up with snow (25).

Section two starts with an epigraph from George Herbert: “O let me rise / As larks, harmoniously / and sing this day thy victories: / Then shall the fall further the flight in me.” Terrifically paradoxical, the second epigraph and its section’s poems (a crown of sonnets called Quarantine) play off the Shakespeare quote as the speaker’s fall accomplishes precisely this flight, a recovery into attending to life and its plenitude. Early in the Bible God declares his name to be Yahweh, or I am that which is, and this definition seems to find its way into the speaker’s terms, and it’s often his attention to what is all around him that brings him a tense stillness, at least temporarily:

but now, to live, to sit somehow, to watcha particle of thought dote on the dust

and dwindle in a little grid of shadow

on the sunset’s patchy rust seems just enough (10).

The flights and falls pervade, as there is also resignation of the utmost: “I am tired god if you’re not // Good enough to kill me let me die” (56). This is Dante’s wood of suicides; this is a journey from lonely frustration to “morning.” It’s a search for answers within and without,a search that is as old as thought, as pattern, as song. And Black’s easily recognizable formal patterns serve the material: as the opening allusion to Shakespeare hints, iambic pentameter and the sonnet are the predominant modes of this collection; they are machines of sound that organize chaos, that give form and purpose and meaning to images, to dreams, to nature, and to life—and yet, like any such form of organizing chaos into arbitrary meaning, they often run from the possibility of chaos, not god, as life’s central force.

Black also employs colons to tremendous effect, colons which syntactically open up possibilities and futures, colons used to prove, explain, define, describe. The book is seeded with them; one sonnet, “Vigils,” actually uses 12 colons. In one apostrophic moment, the speaker says, “I have known you as an opening,” and that is precisely the syntactical essence of the colon: to open up space for explanation, for furthering:

but living is no reasonto continue: everything begins:

and everything is desperate

to extend: and everything is

insufficient in the end:

and everything is ending:

now I can see: even the trees” (14)

The book has a blend of the classical and the contemporary, making references to Herbert, Shakespeare, Dante, Aurelius, Aristotle, and centering around a crown of sonnets—a group of poems wherein the last line of each sonnet becomes the first line of the next—a form that creates its own eternity. Rhyme is a powerful force in this collection: rhyme is memory, is reliving a sound, is re-living. Rhymes, iambs, refrains—the music here is that of repetition, of chant and prayer and ritual; it’s the spill of losing self in sound and tradition. The speaker, already so separated from the almighty “you,” strives—often through moments of pathetic fallacy—to identify with everything earthly:

caught in our palpitating selveswe are furious

machines. Caesar, I have seen

the sea in shelves

of foam and I have known it

as an ancestor (46)

The title, meanwhile, is a fitting representation of the book’s progress from the chaos of suicide and disbelief [“And like the sea, / one more machine without a memory, / I don’t believe that you made me” (31)] to the order, light, and clarity of morning. The storm, like the earthquake, like the sea, exists in the realm of pathetic fallacy—even insurance companies often refer to natural disasters as “acts of god.”

Form is the comfort of tradition, and this book, though mostly dominated by iambs and the sonnet, actually contains variations on the villanelle and pantoum, and even one haiku followed by a prose poem that seem to have awkwardly arrived at the wrong party. Black, in an interview with Melissa Wagoner Olesen of the University of Sand Diego, “eagerly” differentiates between poetry and verse: “poetry is a quality of language much more so than it is a genre or a form.” Well, this book is poetry in verse. Speaking with 32 Poems, Black said, “each of the poems contends with the burden of being, or, more precisely, of being in possession of faculties whose reflex is to make sense of themselves and their surroundings—surely, that is one definition of consciousness.” Though at times solipsistic and captured in their own clever circles, these poems are not self-absorbed because they are so attentive to the world—to its sights and sounds and “machines,” and what could be holier than humble attention to creation?

BIO: Malachi Black’s poems appear in AGNI, Boston Review, Narrative, Ploughshares, and Poetry, among other journals and anthologies. He was born in Boston, Massachusetts, and raised in Morris County, New Jersey. Black holds a BA in literature from New York University and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Texas at Austin’s Michener Center for Writers. The recipient of the 2009 Ruth Lilly Fellowship has also received fellowships and awards from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, the MacDowell Colony, the Sewanee Writer’s Conference, the University of Texas at Austin’s Michener Center, the University of Utah, and Yaddo. He currently teaches creative writing at the University of San Diego and lives in California.