Verdad Magazine Volume 19

Spring 2016, Volume 20

After Hours

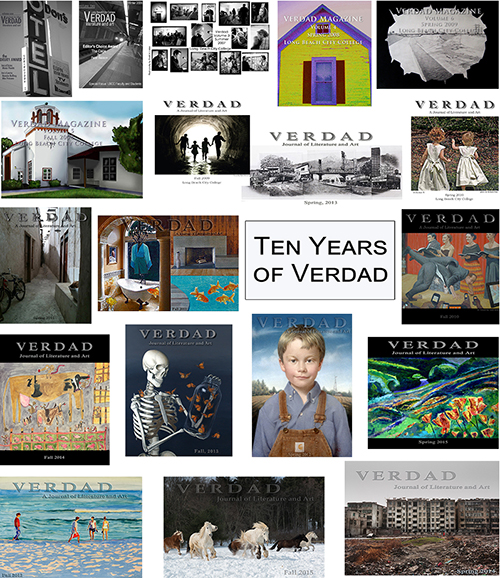

Looking back, it’s been a good ten years as my compatriots and I learned the ropes of online publishing, interfaced with writers and artists from all over the world, produced as high a quality publication as we could; and gradually gained readership. Verdad sees around 300 visitors per month during quiet times, but activity swells to over a hundred visitors a day during the week a new issue is released.

Our editorial staff members have spent countless hours reading and in some cases, soliciting submissions, suggesting changes, and writing reviews and commentary, while at the same time leading busy professional and personal lives.

I, as well, in my role as webmistress, have taken time out from household chores, babysitting grand kids, managing other websites, and dealing with family emergencies and illness, to build every issue of Verdad since volume seven.

With so many obligations filling our days and free time so limited, it is easy to avoid doing anything extra. But Verdad staff members not only work on the magazine, they also work at perfecting their craft and have become creative talents in their own right.

Poetry editor Bill Neumire has a growing family and teaches writing, which as we know requires long hours of grading written assignments and tests; yet in his few spare moments, when he is not reading submissions and writing commentary for Verdad, he writes poetry and authored a first book, Estrus, published in 2013, and is now working on another. One of his lovely poems:

Sleep Studies: Emelia

you have known

no words

in the biblical sense

they have not lain with you

in your window-washed crib

with the letters of your new name

like teeth & shadow abovepetals of the fan

shadow-star the ceiling

all light thrown up

all up disfigured

all down

a pool of footlightsóyou sleep

the dog sleeps

the books all sleep

the way even

things broken

from one great star

sleep, the way sleep

is a needed sort of memory

that one day

stitches itself whole

Art editor Jack Miller, a retired medical doctor, is also an amateur baritone, chocolatier and chef, story writer, art teacher and accomplished artist. He’s always busy, yet finds time to review art submissions and search out new and exciting artists for Verdad. Jack was a Verdad contributor before he offered to be our art editor, and his paintings are featured on the cover and in the art section of volume nine. To the right is one of his paintings, "Count Baldassare Castiglio with Baseball," the count's face displaying "...a bit of anxiety to bring him into the 21st century."

Our inimitable editor-in-chief, Bonnie Bolling, lives part time in California and part time in the Middle East; and despite unreliable internet, nearby anti-government protests and anti-Western violence throughout the region, she oversees every aspect of Verdad and has also authored two prize-winning collections of poetry. Here is an excerpt from a poem, originally published in Verdad volume three, that will appear in her new book, The Red Hijab, forthcoming from BkMk press.

Noon (Al Dhuhr)

after Wislawa Szymborska Lo! God has bought from the believers

their lives and their wealth

because the Garden will be theirs…

—Qur’an 9:111

He’ll put on the vest at noon.

But first, he’ll walk his sister to school

and buy bread for the house at the market.

She waits on a stool in the kitchen.

She’s young—no breasts to speak of yet.

She salts her egg, drinks a cup of milk.It’s only nine fifteen. Still plenty of time.

They walk side by side in the cool breath of morning,

a used book in her hand, ballet slippers—

and the unused vest in his.

The vest’s not heavy, maybe the weight

of a couple of stones or a soccer ball.

The school’s not far—it faces the sea,

a school for girls, with religious women who teach.

His sister kisses his cheek, turns away, goes inside.

Her eyes are blue.

Editor-at-large Frank X. Gaspar leads an active life. He's teaching, most recently as a Ferrol A. Sams Distinguished Writer in Residence at Mercer University in Georgia. He does readings and book signings; as I write, he is in Lisbon for the launch of the Portuguese version of his novel Stealing Fatima and also reading at the Disquiet International Writers Conference and other locations around the city. He still writes both poetry and fiction; and lucky for us, is always on the lookout for new talent to be published in Verdad. Here is his poem, "The Olive Trees" from Verdad volume three and his book, Night of a Thousand Blossoms.

The Olive Trees

In the campus courtyard, in the center of the oldest building

of all the old Spanish buildings, among the white

stuccoed walls, among the ochre tiled roofs, the olive trees

are preparing to leave this world. They are dropping

the dark boles of their olives. They are lightening their burden

as if they might straighten their scarred backs. And the olives

are everywhere under the feet of the young girls and

the young boys and under the shoes of the old men

who are stooped with the weight of their books: olives

like black stars or black fish, staining the brick, drawing

the gnats and the resolute sparrows. The olives are bitter.

You cannot eat them. Here in the sun, on the weathered

bench, I cannot think how Claudius Caesar could have survived

alone on the secret olives he plucked from his trees, when he knew

his wife had poisoned his meals for weeks on end. Yet he outlasted

her resolve. That is the story. But these olives are bitter and

you cannot eat them. And where can they think they are

going, these bent, decrepit trees? See how they cast away

their eyes and ears. And the young, crushing them under

their soft, light feet, and the old, crushing them under

their heavy heels. These trees! See how they think they

have had enough of the earth? See how their shadows

are merely lace, how they leave the morning sun unperturbed?

See how they ready themselves over and over for a new life?

And I, the webmistress—in the midst of my daily routine of cooking, cleaning and computer work—write and validate html, check for browser compatibility, ferret out broken links, and endeavor to make every web page attractive and easy to read (with the assistance of Adobe Dreamweaver, of course). Now I have a new project—that of producing a print edition of Verdad. To help prepare, I self-published my own little book of poems, ones that I'd written during my many years of creative writing classes and which I'd recently revised and added to. The following is an excerpt from a poem about where poems come from:

....Out of the bonfire of words, their poems rise.

They grow from my keyboard and both hands,

from my words made into lines, the lines gathered

in stanzas; they grow out of formal verse and

free verse, out of the rhythm the syllables make;

and the sounds of the words, recurring and diverging,

rhyming and near-rhyming; and the meanings,

literal and figurative, and the vivid imagery evoked;

they feed on memories, on perceptions, on theater of life;

they feed on search for meaning, on engine of emotion,

on flights of imagination, and writing and rewriting;

their poems rise from the heart out of hiding,

from body and breath—the words singing;

and from everything hidden, smoldering inside,

they feed their poems and they rise. They soar free.

from "They Feed Their Poems" (after Philip Levine)

And now we plunge ahead into the future, taking Verdad with us. Let us hope we have many more years of publishing work—poetry, prose and visual art—that is not only beautiful, multi-faceted and touches something inside each of us, but also challenges routine ways of thinking, and inspires us to make new connections and to respond with our own creative contributions. In this way the great river of literature and art slowly changes and evolves with each new addition and comes to reflect the commonalities, differences, and challenges we all face living out our mortal lives on this small planet.

— Rochelle Cocco