Verdad Magazine Volume 8

Spring 2010, Volume 8

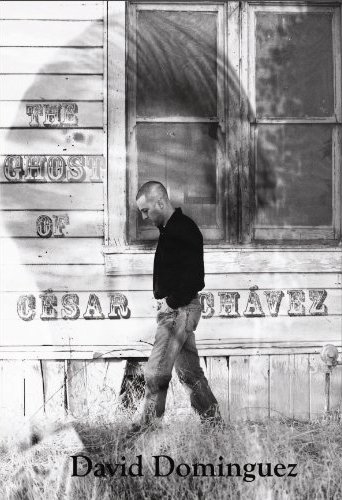

An Interview with Poet David Dominguez

by Bonnie Bolling

Bonnie Bolling: You've just finished your second book of poems, The Ghost of César Chávez (C&R Press, 2010). How has this new book continued your journey as a poet?

David Dominguez: The Ghost of César Chávez is a big deal on a personal level: it means I’m writing, putting poems in envelopes, and sending them off to editors. It makes me feel like maybe I’m actually a writer.

BB: What do you hope the reader will come away with after reading your new book?

DD: While writing this collection, I thought a lot about Pablo Neruda. I read that he wrote his odes for the people who gave him shelter when he went into exile; in other words, he wrote poems for his audience. I knew I wanted my poems to be crafted and accessible. What’s the point of being published if the audience can’t understand and enjoy what you’ve written? When I write poems, I try to focus on subject matter that readers will relate to, and I try to make the narratives as beautiful as possible so that the audience in some way feels moved and is glad they used their valuable time to sit and read my book.

BB: Talk about the poets and poems that have influenced your work.

DD: The first two poems that influenced me were Emily Dickinson’s “The Chariot” and William Carlos Williams’ “The Red Wheel Barrow.” The poems influenced me profoundly because they made me look carefully at the significance of imagery. When I write, I always see horses’ heads pointed towards eternity, wheel barrows, rain water, and white chickens. I’m especially interested in imagery because I believe that images are powerful because they work allegorically. Since images, both concrete and romantic, work on multiple levels, they push a narrative forward.

BB: What can you say about Master of Fine Art programs in creative writing?

DD: If I were giving advice to a writer who is in the process of looking at MFA programs, I would tell him to gather his most favorite books of contemporary poetry and to read the author’s bios. Then, I would tell that young writer to apply to the MFA programs where their favorite poets currently teach. Secondly, I would encourage him to apply to programs that offer 50% craft seminars and 50% workshops. Writing workshops are important, but I think you learn more about writing in seminars. A craft seminar is when you READ poems by proven authors and break down lines word by word until you understand what tools make the poems successful. In workshops, the conversations focus on “why I like it” or “why I don’t like it,” and sometimes, the tone of these discussions becomes negative as young writers try to prove their worth by putting each other down. At the University of California at Irvine and University of Arizona, I took several poetry workshops with Michael Ryan and Steve Orlen respectively, and these were wonderful experiences because both of these professors taught craft, and for that I am eternally grateful. Most workshops, however, focus on critiquing, which is why I believe in the importance of the craft seminar.

BB: You taught here, at LBCC, for a while. What was your experience in getting work after finishing your degree?

DD: I graduated with my MFA in 1997. As graduation approached, I started thinking about finding a job. I knew Southern California had several community colleges. I called human resource offices and was told to check with the department chairs. I found out their office hours and locations, and as soon as I graduated, I started walking into offices and said, “Hello, my name is David Dominguez, and I’ll teach anything, anywhere, anytime.” I had no idea what I was doing, but because I was willing to work hard and could figure things out for myself, I had no trouble finding part-time jobs. I taught two classes at Long Beach City College, two classes at East Los Angeles College, and one class at Los Angeles City College. Eventually, I was hired full-time at Long Beach City College. At all three of these community colleges, I was lucky enough to be mentored by experienced faculty, which was invaluable.

BB: Referring to your sequence of prose poems in The Ghost of César Chávez, can you talk about the importance of ancestry in your work?

DD: Ancestry is an important theme in my work. I find myself returning to this subject because understanding my ancestry helps me know myself. As a poet, understanding the self is very important. The better I understand myself, the clearer my poems become, and writing clear poems shows respect for the reader. Through my ancestry, I’ve discovered hidden worlds. The image of my great great grandfather standing on the steps of his church as he played his violin to welcome his flock is am incredible moment. The image of my father sitting in San Francisco’s Masonic Auditorium and realizing a miracle as John Coltrane says, “Good evening” is sublime. Those images are worlds unto themselves. Worlds that will inspire who knows what in my writing. By studying my ancestry, I have been exposed to tastes, sounds, images, smells, and surfaces that I may have never known.

BB: Two of your poems were published by The Southern Review. Can you talk about your strategy that led to this publication?

DD: I send poems to as many reputable journals as I can—especially the most prestigious ones, such as The Southern Review. At home, I keep records so that I remember which poems I’ve sent where. You have to be hard headed. I’ve been rejected by the same periodicals four or five times. I’ve received more than one rejection letter on the same day. I just keep revising and listening to writer friends who read my work and make suggestions so I have reasons to stuff paper into envelopes so I can be rejected again. In general, I only submit to journals that accept simultaneous submissions. Also, I only submit to journals that publish at least some narrative poetry. To all the editors who have been kind enough to publish my work, “¡Gracias!”

BB: Talk about the title poem of The Ghost of César Chávez, the seed that began it, and your process to bring it to completion.

DD: A few years ago I was asked to participate in a reading honoring César Chávez. I knew I wanted to write a poem specifically for this event, so I started reading as much as I could about Chávez. What struck me most was Chávez’s kindness. He cared so much about the campesinos that at 61 he started his final hunger strike. This last hunger strike haunted me, and most of all, it made me feel ignorant. I was at the University of California at Irvine when Chávez died. I heard something about it on television, but I didn’t care. How could I not care? This feeling of ignorance and Chávez’s kindness fueled the poem. In the poem, the narrator longs to feel close to Chávez and does so through the poem itself.

BB: You are a co-founder and poetry editor of a new literary magazine, The Packinghouse Review. Talk about how you choose poems, your particular aesthetics, and the future of poetry.

DD: I’m looking for poems that are well crafted. Next, I want poems that are accessible. Usually, I select poems that are narrative and image driven because I believe that those poems are more understandable. I like poems that are searching for the sublime, poems that have wild turns, and poems that have a strong sense of the physical landscape: I want Sagittarius, not stars; lemon trees, not trees; Kings River Road, not road. I love poems about music and food. Poems about the act of reading and writing. Poems that explore the lives of artists. Poems with a sense of humor. And poems that explore ancestry and culture. Off hand, I’m inspired by the work of William Carlos Williams, Mary Oliver, James Wright, Philip Levine, Larry Levis, Christopher Buckley, Gary Soto, and Frank Gaspar, to name a few, which might reveal what aesthetic I’m looking for when I read submissions. The reason I want readily accessible poems is because poetry needs readers to survive. If the reader can’t figure it out, they’re going to toss it aside and rent a DVD. Who can blame them? The reader’s time is more valuable than the writer’s time. So what is the future of poetry? The future of poetry depends on the poet. As long as the poet respects his audience and writes for his reader more than he writes for himself, poetry will flourish, for the result will be beautifully crafted poems that are wise and entertaining*. It is my hope that The Packinghouse Review will give hard working poets the opportunity to show how brightly poetry can shine across the page.

______________________________

*I’m echoing the words of Larry Levis. Please see his fine lecture “War as a Parable and War as a Fact: Herbert and Forché,” page 160, in A Condition of the Spirit, edited by Christopher Buckley and Alexander Long, (Eastern Washington University Press, 2004).

BIO: David Dominguez’s first full-length collection of poetry, Work Done Right, was published by the University of Arizona Press, 2003. His second collection of poetry, The Ghost of César Chávez (C and R Press, 2010) is newly released.

BIO: David Dominguez’s first full-length collection of poetry, Work Done Right, was published by the University of Arizona Press, 2003. His second collection of poetry, The Ghost of César Chávez (C and R Press, 2010) is newly released.

Dominguez’s poems have been published in magazines and journals, such as Bloomsbury Review, Crab Orchard Review, Poet Lore, and Southern Review.

His work has been anthologized in The Bear Flag Republic: Prose Poems and Poetics from California; Breathe: 101 Contemporary Odes; Highway 99: a Literary Journey through California’s Great Central Valley, 2nd edition; How Much Earth: the Fresno; and The Wind Shifts: New Latino Poetry.

He teaches composition and poetry writing at Reedley College and is the co-founder and poetry editor of The Packinghouse Review (www.thepackinghousereview.com).